Remembrance is a poignant reminder that Canada currently has more than half a million veterans. Whether they served in times of war, conflict or peace, behind every veteran is a story of service, dedication, courage and sacrifice.

listen to their words read stories Books of Remembrance memorials Miltary Service Recognition Books Remembrance prompts us to recognize that

veterans face unique challenges and need our compassionate support. The

Royal Canadian Legion) officially adopted the Poppy as its Flower of

Remembrance on 5 July 1921.

4 years, 3 months and 14 days of Brutal Conflict

In the Aftermath of the Great War

The Human Face of War

The Language of Remembrance

Canadians Understand and Embrace Remembrance

A Century of Purposeful Respect and Gratitude

* Please be warned that links from this section may contains graphic language and images of war.

The Great War of 1914-1918 was the largest and most brutal conflict the world had ever experienced. The carnage was incomprehensible to everyone. An idealistic premise emerged, suggesting the conflict's immense scale and devastation would make future wars impossible.

World War I was a war between the Central Empires and the Entente. It started on July 28, 1914, when Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia. The Central Powers was an alliance between the German Empire, Austria-Hungary, the Ottoman Empire, and the Kingdom of Bulgaria. The Entente was an international military coalition of countries led by the French Republic, the United Kingdom (with its British Dominions) and the Russian Empire joined by the Kingdom of Italy and Empire of Japan before the end of 1914. The United States became an associated power near the end of the war in 1917.

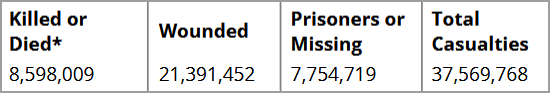

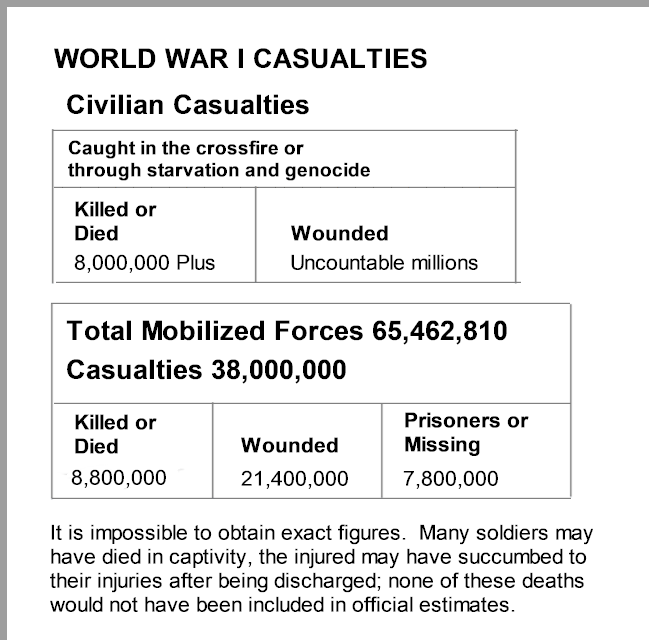

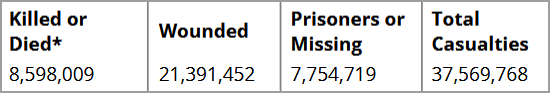

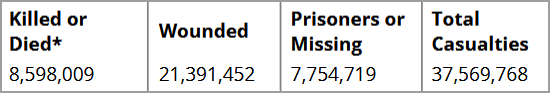

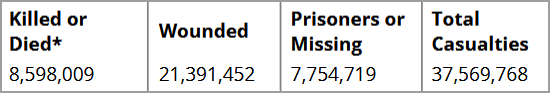

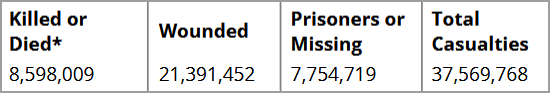

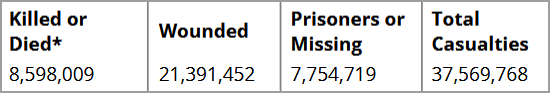

After just five months of fighting, the number of dead and wounded

exceeded four million men. In the ensuing 47 months of fighting, the death and destruction was increasingly atrocious. Air stifled by fumes of gas and burning thatch hung heavy over fire-swept

terrain and mud-scapes of devastation. Ten million refugees were forced to flee their homelands. The death toll was shocking and deplorable - per day 6,000 soldiers died. Day after day casualties among civilians mounted in dizzying numbers. In unprecedented numbers, soldiers lost limbs from shell explosions and machine gun attacks . Armies and medical professionals were pushed to their

limits by the sheer scale of suffering. The types of injuries were not

necessarily new, but they occurred on an unprecedented scale.

By 1918, hunger, exhaustion, demoralization

and defeats signaled the end of the hostilities. The Entente agreed to an armistice with Bulgaria on 29 September,

the Ottomans on 30 October, and the Austro-Hungarian Government on 3

November. Finally, that that same month the German faction sought a ceasefire and met with the Entente Powers in Compiègne, France. At 5:10 AM on the morning of November 11 an armistice was signed which would formally cease hostilities and hopefully bring an end to the First World

War. To allow time for the intelligence to reach combatants the agreement specified that the armistice would take effect that day at 11:00 am.

World War One had been brutal, claiming the lives of more than 16 million people, military and civilian. On November 11 alone, the day the armistice was signed there were nearly 11,000 casualties - dead, missing and injured. In the face of such enormous loss and

horror, claims of victory or defeat seemed irrelevant, disrespectful, sacrilegious.

The war was vicious, impersonal, indiscriminate. People of all ages, races, all

social classes were affected. So when the war ended there was relief and cause for celebration. For some the end of the war was a period of great excitement, fathers and brothers returning from high adventures in exotic places. Those, whose loved ones

never came home, remembered it differently as a time of tragedy and unbearable sorrow. Grief was palpable and pervasive. The nature of death, the absence of a body, or the specter of war had disrupted traditional mourning practices. People openly grieved together.

Overshadowing the celebrations was an abundance of sadness, economic hardship, widespread destruction, the trauma of the violence and uncertainty.

For many millions of people the suffering did not end with the armistice. Ten millions civilians were displaced. Civilians brutalized during the war were trying to live with the trauma. Most soldiers who survived the fighting were trying to to contend with long-lasting injuries, lifelong pain or the haunting trauma from both the physical and mental scars of prolonged combat.

During the war many people saw war through the lens of a camera or a journalist’s account of fighting. They knew the size and strength of a military or the vital outcome of a battle, the abstract - absent the imagery. However, in the aftermath of WWI, in the face of returning soldiers, the savagery of the war was finally unmasked. People finally saw the visceral picture of war, one they were not supposed to see as millions of soldiers returned home blind, with amputated limbs, bodies burned and horribly disfigured. Astonishing numbers of soldiers were shell shocked (PTSD) which manifested in amnesia or some kind of paralysis or inability to communicate. The human costs become undeniable through powerful

and personal accounts. The bereaved, surrounded by such reminders, imagined what their fathers, sons, daughters, sweethearts had experienced in battle and death.

Amidst such visual and emotional reminders, it was impossible to ignore the stories of individual suffering.

In trying to comprehend the human face of war, people grieved together, and understood that life might not ever return to normal. Even as the grieving subsided, people could not forget. Haunted by the understanding of the new language of Remembrance, people around the world began to gather annually to give respect and honour the brave souls who left home to courageously volunteer

for the cause of freedom and peace.

The

armistice signed on November 11 was celebrated as the date of the end of the

First World War.

It was named a holiday in several nations. Some nations adopted other names: Veterans Day (USA), Poppy Day (South Africa, New Zealand), Some nations choose to commemorate their war

dead on Remembrance Sunday (nearest November 11) and some choose the

anniversary of other notable events in World War I.

In cities and small town around the world, memorial associations were organized and money was raised to erect lasting monuments to the men and women who had served in the war. The public came together in such truly astonishing numbers, reflecting the passion of public sentiment for the Great War that had dramatically changed the world.

In the aftermath of World War One and its carnage celebrations of victory in Canada were subdued and replaced by solemn memorials to honour those that lost their lives at sea or on the battlefield and did not come home from The Great War.

The guns had been silent for one year when King George V urged Commonwealth countries to observe two minutes of

silence on Armistice Day, designated as the second Monday in November. In 1921, the Canadian Parliament passed an Armistice Day bill to

observe ceremonies on the first Monday in the week of 11 November. Ten years later Parliament decreed

that the newly named Remembrance Day would be observed on 11 November.

Reflecting a fundamental change in the national consciousness, in communities across Canada, people gathered to honor the 66,000 young Canadians who sacrificed their lives in the Great War. They were ordinary Canadians who made extraordinary sacrifices. They fought for four years to safeguard a way of life,

shared Canadian values and the freedoms we enjoy today.

Canadians discerned that the country owed a collective national debt to the ordinary

soldiers, mostly young men, who had lost

their in battle, and moving forward this would forever be an obligation of future generations, acknowledged by the simple act of remembering the soldiers’ sacrifice.

We must remember. If we do not, the lives of those Canadians who made the ultimate sacrifice will be meaningless. They fought and died for us, for their homes and families and friends, for a collection of traditions they cherished and a future they believed in; they died for Canada. The meaning of their sacrifice rests with our collective national consciousness; our future is their monument.

Heather Robertson, A Terrible Beauty, The Art of Canada at War. Toronto, Lorimer, 1977.

Canadians embraced the new language of remembrance through the adoption of the poem "In Flanders Fields" as a symbol of our Remembrance and by wearing poppies in advance of Remembrance day as a visual pledge to never forget those who served and sacrificed.

The

national ceremony for Canadians is held at the National War Memorial in Ottawa on the eleventh day of the eleventh month. The Governor

General of Canada presides over the ceremony. It is also attended by the Prime

Minister, other government officials, representatives of Veterans’

organizations, diplomatic representatives, other dignitaries, Veterans as well

as the general public. At "the eleventh hour" a trumpet calls "The Last Post" after which there is "two minutes of silence" to express our gratitude to 2.5 million Canadians who served throughout our nations’

history; to honour those that lost their lives throughout history in any

conflict; and to acknowledge and thank the men and women who continue to serve.

Likewise, in communities across the country, at the "eleventh hour" it is a national tradition on for Canadians to act in fellowship. Whether from work, school, home or at a Legion ceremony we pause and bow our heads in a two-minute silence. We stop to

remember and honour those brave souls who left home to courageously volunteer

for the cause of freedom, peace, and a future they believed in. We exist as a proud and free nation because of the sacrifice made by those who served.

Remembrance Day is a federal statutory holiday in Canada. It is a statutory holiday in

three territories (Yukon, Northwest Territories and Nunavut) and in six

provinces (British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan, New Brunswick, Prince

Edward Island, Newfoundland and Labrador), and observed in Manitoba, Ontario and Quebec

Over 650,000 Canadians and Newfoundlanders served in uniform. Over 172,000 were wounded in battle and ,ore than 65,000 brave Canadians find their final resting place in the lands they helped to free. Their significant contributions and sacrifices resulted in Canada earning a separate signature on the Treaty of Versailles, which officially ended the war. Time has surely not diminished their legacy.

HMCS WetaskiwinHMCS Wetaskiwin was Canadian Flower-Class corvette. It was warship that served in World War One. Its journey along with the naval experiences of its crew in the Atlantic war against Kreigmarine submarines was not glamorous and made no compelling history. It is, however, deeply intertwined with the challenges, sacrifices, achievements and legacy of the long-drawn-out Battle of the Atlantic. This warship's chronicle gives an accounting of those events and mirrors the story of the men and women who served to make an Allied victory possible.