War Duty - Convoy Escort in the Battle of the Atlantic - 1940-1946

Pendant #175

6 Officers and 79 Crew

201.1 ft

950 tonnes

Canadian Service 1940-1946

6 Officers and 79 Crew

201.1 ft

950 tonnes

Canadian Service 1940-1946

HMCS Wetaskiwin (Pendant Number K175) was a Flower Class corvette serving with

the Royal Canadian Navy (RCN), as a convoy

escort in the Battle of the Atlantic during World War II. She served most of her deployment in the unforgiving North Atlantic Ocean where Kriegsmarine's U-Boats patrolled the shipping lanes to attack shipping convoys in order to cripple vital supply lines of food, oil, equipment, supplies and raw

materials for Britain, Occupied Europe and the Soviet Union. Millions of lives were at stake and the corvette was a near-perfect anti-U boat weapon.

HMCS Wetaskiwin was one of 122 Flower Class corvettes built in Canada.

While not as prominent as larger warships, HMCS Wetaskiwin and other Canadian-built Flower Class corvettes became the mainstay of Allied convoy protection. They escorted thousands of ships from the Aleutians to the Caribbean and Mediterranean, from the East Coast of North America to the Artic, Iceland and Northern Ireland. They hunted submarines and engaged in combat. Along the way they rescued hundreds of survivors from ships that had been torpedoed. Corvettes became the an obvious presence in a convoy, safeguarding the lives of thousands military personnel, civilians, valuable ships as well as cargoes.

First Sea Lord Admiral Sir Dudley Pound, is quoted as saying, The Canadian corvettes solved the

problem of the Atlantic convoys.

This statement is singularly noteworthy considering that in 1939, Canada had a fledgling navy.

The Royal Canadian Navy personnel numbered less than 2,ooo and it possessed six destroyers, five small minesweepers, two training vessels left over from the First World War and about three dozen ocean-going Canadian-registered merchant ships. Canada's convoy escort duties commenced at the outbreak of war. By early 1940 Canadian destroyers were engaged in battle in European waters. Still, no

one would have predicted that, from this tiny beginning,

97,600 men and 7,100 women would signed

up for the navy and over 330 warships would be commissioned. By 1945, the Royal Canadian Navy had the third largest allied fleet in the world.

Canada and Newfoundland's participation in World War Two was virtually unquestioned. Men and

women rushed to enlist and were a major factor in the Allied victory.

Due to the urgency of war, Canada's navy recruits received rudimentary training before being assigned a position on a battle ship. To serve aboard a corvette like the Wetaskiwin required unflinching courage and tenacity. It was at sea that raw recruits turned into real sailors and acquired the technical proficiency to do their job and the discipline to live at sea in cramped adverse conditions. Along the way they found the spirit and determination to persevere. No matter their age, the courageous men and women who served steered the RCN through some of the Second World War's toughest times and in combat played a vital role for the duration of the war, leaving the Royal Canadian Navy with a distinguished legacy.

The journey of HMCS Wetaskiwin, its early maneuvers, war missions, battles, along with the naval experiences of its crew in the Atlantic war against Kreigmarine submarines was not glamorous and made no compelling history. It is, however, deeply

intertwined with the challenges, sacrifices, achievements and legacy of the long-drawn-out Battle of the Atlantic. This warship's chronicle gives an accounting of those events and mirrors the story of the men and women who served to make an Allied victory possible.

It is an enduring story that has its niche in Branch 86 of the Royal Canadian Legion. It is not just for history buffs. HMCS Wetaskiwin's legacy is one of bravery, resilience, and community spirit.

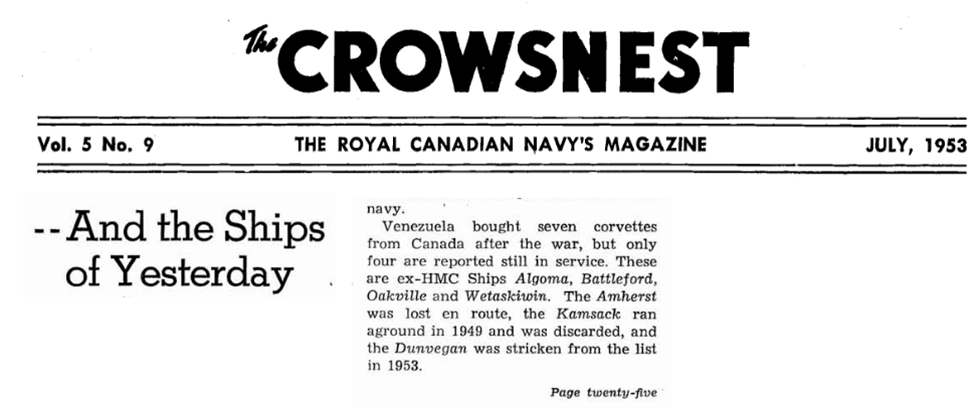

by "Sanko"

You can choose to read some background information about WWII that triggered the launching of HMCS Wetaskiwin K175 by simply expanding a heading below. Alternatively, you can scroll to the next section to begin reading this warship's story.

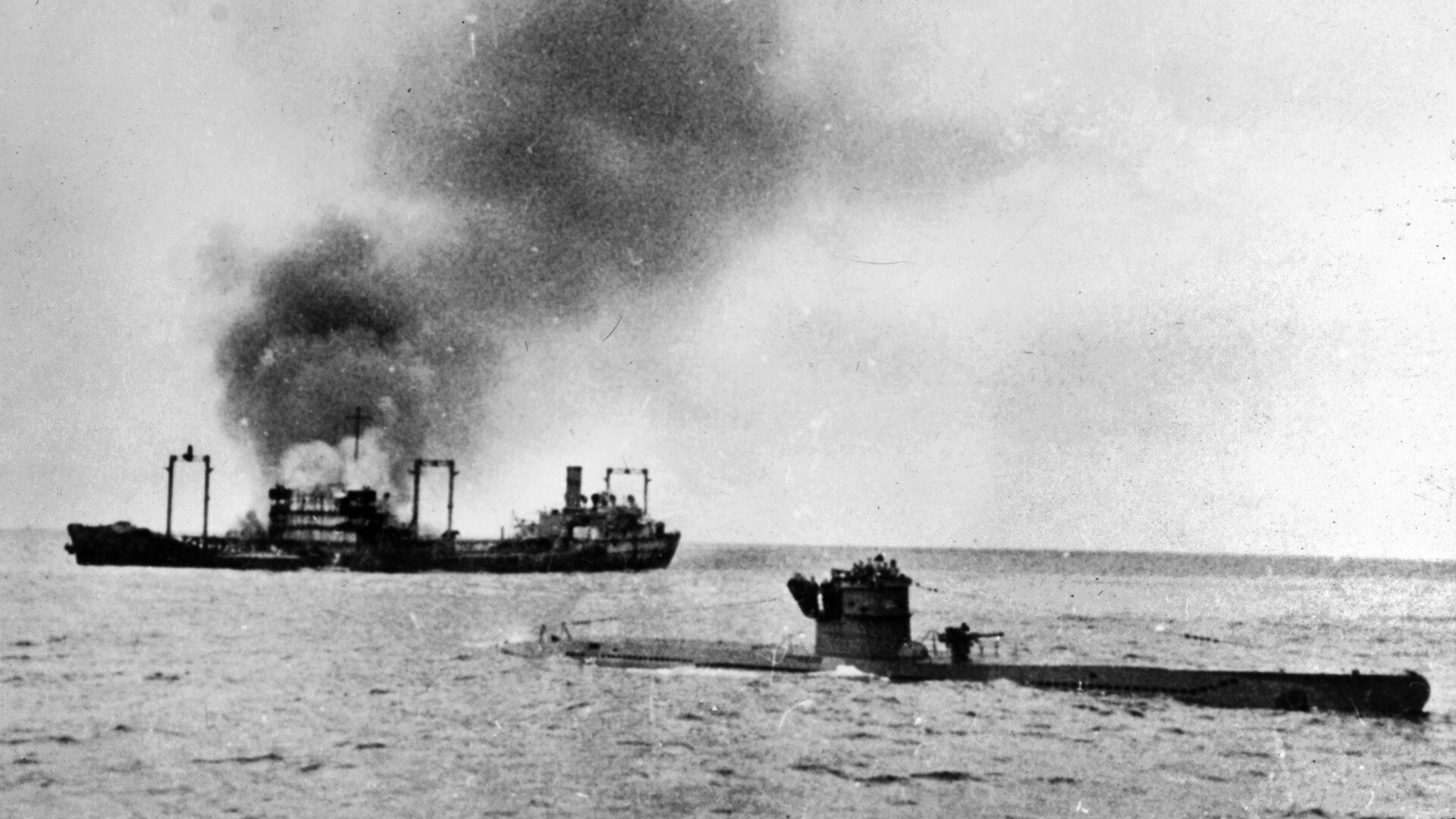

On September 23, 1939, eight hours after Britain and France declared war on the German Reich, the Kriegsmarine struck hard. German submarine U-30 patrolling the Western Approaches off the coast of Ireland torpedoed the SS Athenia, a British passenger ship working between Canada and he United Kingdom, killing 117 passengers and crew. Three-quarters of her passengers were women and children. Among those that lost their lives - 54 were Canadian and 28 were US citizens)*.

The Battle of the Atlantic had begun, and from that evening to the dusky hours of Monday, May 7, 1945, it never ceased.

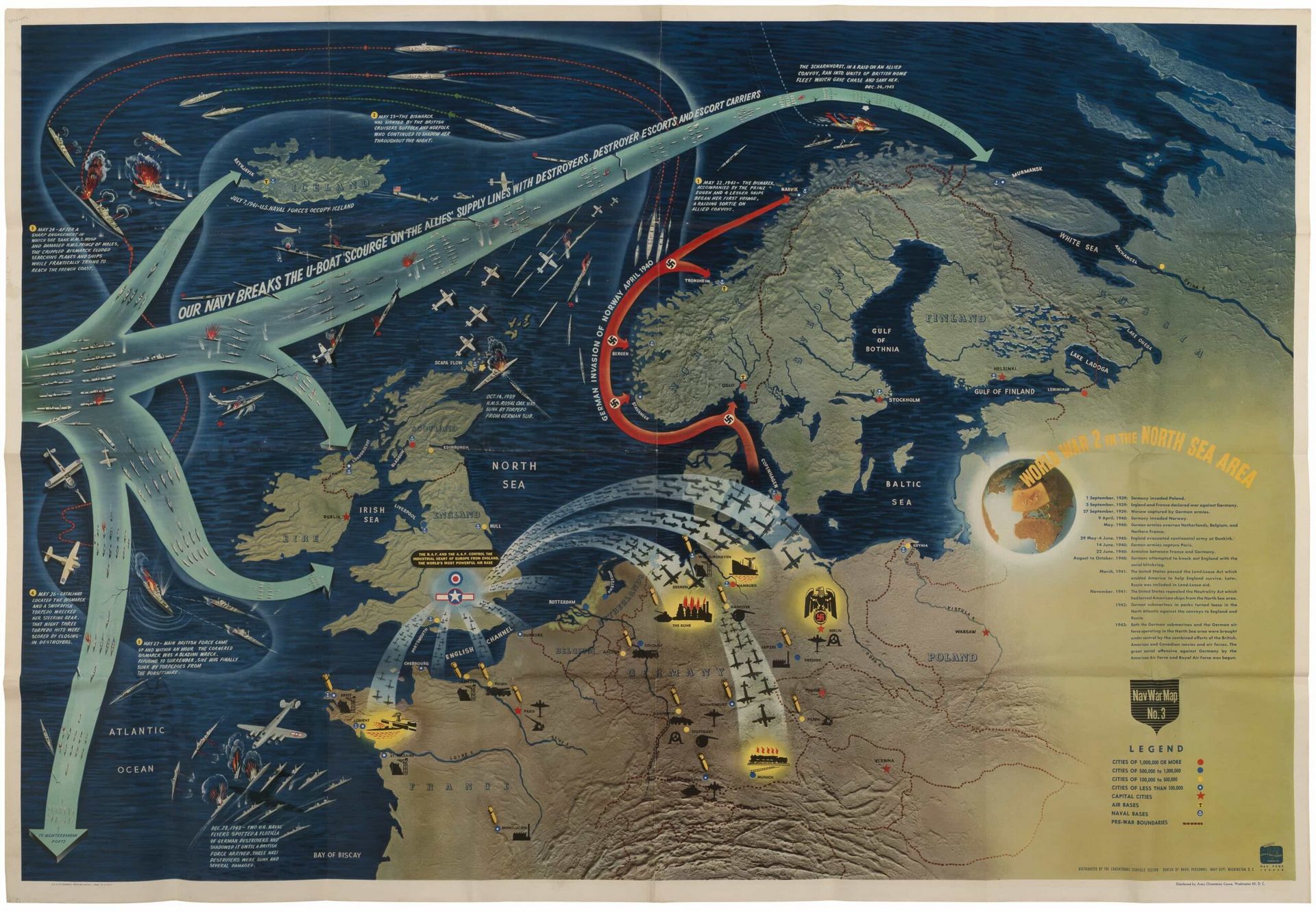

One gets the the impression of one major battle, relentless clashing. It actually was a series of ferocious, grinding campaigns waged sporadically across the Atlantic Ocean and touching three continents (North America, Europe, and Africa) as Allied navy commands struggled to protect trans-Atlantic shipping from German submaries that terrorized convoys, crippled crucial supply lines between North Americ and Europe, making it the longest, largest, most arduous and complex naval battle in history.

The Battle of Britain lasted 68 months. There was significant cost in the number of ships sunk until the Allies gradually gained the upper hand. Victory was costly. More than 70,000 allied seamen, merchant mariners and airmen lost their lives at sea and have no known grave.

For the whole of the World War II the Royal Canadian Navy (RCN), merchant navy and air force were engaged in the Battle of the Atlantic (1939-1945) with the RCN playing a crucial role against the sea and air attacks perpetrated by German Reich.

* Whether the sinking of the Athenia was deliberate or the U-boat captain mistakened the liner for an armed cruiser, the attack on an unarmed passenger liner was a clear breach of international protocols. Conspiracy theories circulated. However, the mere presence of a U-boat off the coast of Ireland was was a clear indication of Hitler's maritime intentions.

**In 1917, a German submarine torpedoed and sank the first SS Athenia, also just off the coast of Inishtrahull, Ireland. Rockall Bank, an area of raised seabed a few hundred km from the Irish coastline.

In the spring of 1940, the war in

Europe took an ominous turn. After the fall of France on 17 July 1940, Britain and her Commonwealth Allies were left to defend against the Axis (German Reich and Italy) taking the whole of Europe. With its isolation from Europe and its lifeline to European imports completed cut off, Britain was more dependent upon goods shipped from North America. The

British required more than a million tons of food, oil, equipment, supplies and raw

materials to be shipped in each week.

Allied Response and Early Convoy Strategies

German Reich's Perspective

From the German Reich's perspective, an Axis blitz on allied shipping would choke off vital supplies and force Britain into surrendering. With France and the low countries defeated, Germany had control of the entire coast of Europe which gave their Kriegsmarine (German Navy) direct access to the Atlantic.

The Kriegsmarine (German Navy) went on the offensive using a range of warships, U-boats, auxiliary cruisers and long-range aircraft. Their navy and airforce set out

from every harbour and airfield in western Europe to sever the lifelines to

Britain. They bombed British shipping ports and deployed surface raiders, warships, merchant raiders, U-boats and aircraft to patrol critical supply routes, especially in the Western Approaches. Submarines lurked in the Black Pit.

One German battleship, the Admiral Graf Spee alone, sank nine merchant

ships totaling 50,000 tons between September 30 and December 7 of 1939. Their surface raiders caused havoc and long-range Focke-Wulf Condor

200 bombers sank 580,000 tons of British shipping the following

year (1940). U-boats, their deadliest ocean predators, lurked beneath the

Atlantic ocean hunting for merchant vessels.

Merchant Ships Easy Prey

Prior to the war, merchant ships crossed the Atlantic singularly or in pairs between Halifax and New York to ports in England or Northern Ireland. The only protection available against a merchant raider might be an armed yacht. Merchant vessels were heavily loaded, low, slow in the water and vulnerable. These ships were easy prey and faced constant threat from warships and submarines.

Establishing and protecting shipping lanes

did not only depend on the success of the Armed Forces but also a massive

personal risk to the civilians sailing under an Allied flag. Remembering that in World War I German

submarines had brought their country to within three weeks of starvation, the British Admiralty wasted no time in organizing a convoy system to protect merchant ships.

Canada immediately responded.

The Royal Canadian Navy only had eleven combat vessels at the time. It rushed four destroyers to the British Isles to protect convoys on its western shores and used its other vessels to protect the convoys on this side of the Atlantic.

Canada Created Merchant Navy

When war was declared, the Canadian government immediately moved to pass laws to create the Canadian Merchant Navy to provide a workforce for wartime

shipping. Facing high casualties rates and showing undeniable courage, 12,000 men and women, aged from fourteen through to their late seventies, rushed to enlist in Canada's Merchant Navy. The Merchant Navy was considered a fourth

branch of the Canadian military alongside the Royal Canadian Navy, Canadian Army, and the Royal Canadian Air Force, and suffered the

highest casualty rate of the four. Rear Admiral Leonard W. Murray reported: The Battle of the Atlantic was not won by

any Navy or any Air Force, it was won by the courage, fortitude and

determination of the British and Allied Merchant Navy.

Early Convoy Strategies in WWII

The British Admiralty requisitioned anti-submarine escort groups to protect the convoys in the Western Approaches and convey ships to a zone in the mid-Atlantic beyond enemy U-boat range. British defence resources being spread thin, the Royal Navy had a critical shortage of escort vessels. They pulled together destroyers and old generation naval vessels. They militarized yachts, passenger liners, survey ships and fishing trawlers - any vessel that was sufficiently seaworthy.

Since most of these vessels did not have the range or endurance to accompany convoys through the mid-Atlantic, the Royal Navy utilized a relay system where one escort group protected a convoy to a designated meeting point and handed protection over to another escort group to accompany the convoy from England to Ireland and across the Western Reaches. However, routing of trans-Atlantic convoys required meeting points beyond the range of anti-submarine sea vessels

The convoy had some protection from the air. An aircraft could cover a larger area than any warship and could

pounce on an unsuspecting submarine with deadly effect before it could dive out of harm's way. However, the British Admiralty and Allied Coastal Command was perpetually short of aircraft for trade defense, because the mainland bomber offensive was prioritized. The aircraft allotted to convoy protection were effective in limiting the places U-boats could attack a shipping convoy, but lacked the fuel range to provide air cover through the central part of the Atlantic Ocean.

Between ports near naval bases, such as at Halifax, Gaspe or Quebec City in Canada or between Liverpool, Portmouth, or Londonderry in the United Kingdom escorting a convoy was less complicated. However, efficient routing of trans-Atlantic convoys required meeting points beyond the range of anti-submarine sea and air escorts on both sides of the ocean.

For the whole of the World War II Canada's Royal Canadian Navy, Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) and Canadian Merchant Navy were engaged in the Battle of the Atlantic (1939-1945). The RCN playing a crucial role against the sea and air attacks perpetrated by German Reich.

There was a dangerous zone in the mid Atlantic that no plane from Canada, Ireland, Iceland, or Britain could reach. It was a zone about 300 kilometers wide called the Mid-Atlantic Gap where convoys steamed for four to five days without land-based anti-submarine air escort before being picked up by the Allied air escort on the other side. In this undefended zone slow-moving convoys were vulnerable.

Toward the end of 1940, Kriegsmarine, Germany's U-boat command, was able to exploit this weakness because their submarines were able to extend their range of operations beyond the Western Approaches and further into the mid-Atlantic than the previous months of the war. In pursuit of destroying vital convoys that were Britain's lifeline, U-boats steadily patrolled this undefended zone. It was excellent hunting ground.

To the 4,000 ships convoyed across the Atlantic in 1940, this zone of the Atlantic without air support was dangerous. Sailors dubbed it The Black Pit because that was where U-boats inflicted the most damage.

The Allies were in dire straights. The

Enigma Code had not yet been cracked, no fixed ground radar station had yet been established for aircraft, breakthroughs in sonar, radar for ships, HF/DF (radio-goniometry) were months from being highly functional, anti-submarine escorts lacked the

endurance to accompany convoys through the mid-Atlantic. While the convoy system limited losses, Great Britain and her allies had a lack of escort ships.

Meanwhile, Hitler’s U-Boats were terrorizing the shipping routes. German U-boats were superior weapons due to excellent technology and a highly skilled, well-trained crews. U-boats sank 199 merchantmen and a third of the Royal Navy’s battleship strength in the first months of the war. By the end of 1940, U-boats had sunk almost 2 million tons of Allied shipping in the Battle of the Atlantic. Shipping losses were staggering and the loss of life among merchant seamen and allied sailors was tragic.

Merchant ships were being sunk faster than they could be

replaced. Whereas, the German Reich launched eight U-boats for every one they lost and had the capability to deploy a small but steady stream of warships to the Atlantic.

Kriegsmarine command had the advantage of its enigma machine for communication and it also implemented wolf-pack hunting tactics. Roving packs of submarines spaced at a distance from each other patrolled for convoys. Once a convoy was spotted the U-boats in groups of 6-20, moved in closer and waited patiently at a distance for darkness, when they were virtually

undetectable. U-boats torpedoed unprotected convoys indiscriminately and with impunity.

The U-boats picked off solo ships and

stragglers and made bold, single-handed attacks on convoys. These young aces,

the German elite, raced each other for tonnage sunk. German naval commanders later referred to the period July to September 1940 as "the happy time."

~ Veterans Affairs Canada

After a major defeat in October 1940 when a critical convoy from Halifax to Liverpool was attacked by five U-boats - twenty of thirty-five cargo vessels were sunk there was imminent danger that deprived of food and oil millions of people would perish and Great Britain would fall without a single Axis soldier stepping foot on their island.

The German Reich had the upper hand. While a far greater threat to ships at sea, which put the supply link between North America and

Europe at even greater risk, there was cause to fear that U-boats would eventually launch attacks on land-based facilities or harbours in Eastern Canada or Newfoundland.

Before the start of World War II, Britain's Royal Navy was deemed the strongest navy in the world with naval bases in all corners of the globe and the fact that they had built the largest number of warships and had as many ASDIC warships in service as all the other navies of the world combined. It was a navy prepared to jolt into action.

Due to the pace of global events the expansion of the German Reich threatened the lives of millions of people United Kingdom, Occupied Europe and the Soviet Union. There was an urgent need for patrol and escort vessels to protect the Atand lantic shipping convoys which were transporting vital supplies - food, oil, equipment, supplies and raw

materials. German U-boats were sinking 1,000 tons of Allied shipping every hour.

Warfare is a large and urgent enterprise. Naval engagements between the Allies and German Reich were usually of short duration; but warships such as destroyers, frigates and submarines are not put into action quickly. They are the product of a years of functioning organization, time consuming preparation, scientists and engineers frantically working, financing and resource procurement before construction even begins. Then of course there is the recruitment and training of manpower. In other words, even a rushed naval programme might not materialize within two to three years.

To meet its urgent need for patrol and escort vessels, Britain devised a plan to boost naval defence using Flower Class Corvette's. Shipbuilding yards in the United Kingdom were at capacity. Canada’s small-yet-professional navy sought to expand its fleet

quickly. By early 1940, the Royal Canadian Navy had Canada's ship building program underway.

Beyond building the ships, Canada played a major in the Battle of the Atlantic and the rise of the Royal Canadian Navy was due to Canada building Flower-Class Corvettes.

At any one time there could be a dozen

convoys (up to 20,000 people aboard) crossing the Atlantic at the same

time.

All convoys were classified according to speed and destination. Convoys designated as HX were British bound convoys carrying explosive cargo (oil, munitions) expected to sail from Halifax to England in 15 days.

A slow convoy was the worst assignment. It was more vulnerable to attack than fast moving convoys. Merchant vessels were older, weather-beaten, and prone to breakdown. Slow convoys were routed north toward Iceland which was a longer rougher passage by about another 5-6 days. Moreover air support from Iceland was limited.

H (Homebound) - convoys bound for Britain

O (Outbound) - convoys returning to Halifax or Sydney

HX - fast homebound convoy carrying explosive cargo (oil, munitions)

sailing from Halifax or New York - typically made the crossing to from

Halifax to England in 15 days.

SC - slow convoys, regardless of destination sailing from Sydney, Halifax or

New York, their common speed 7 knots. From Halifax to Liverpool took about 20

days.

ON: westbound convoys sailing from Great Britain to North America

JM - convoys from British ports to Murmansk

PQ - convoys from Nova Scotia via Iceland to Murmansk

M - convoys sailing to the Mediterranean

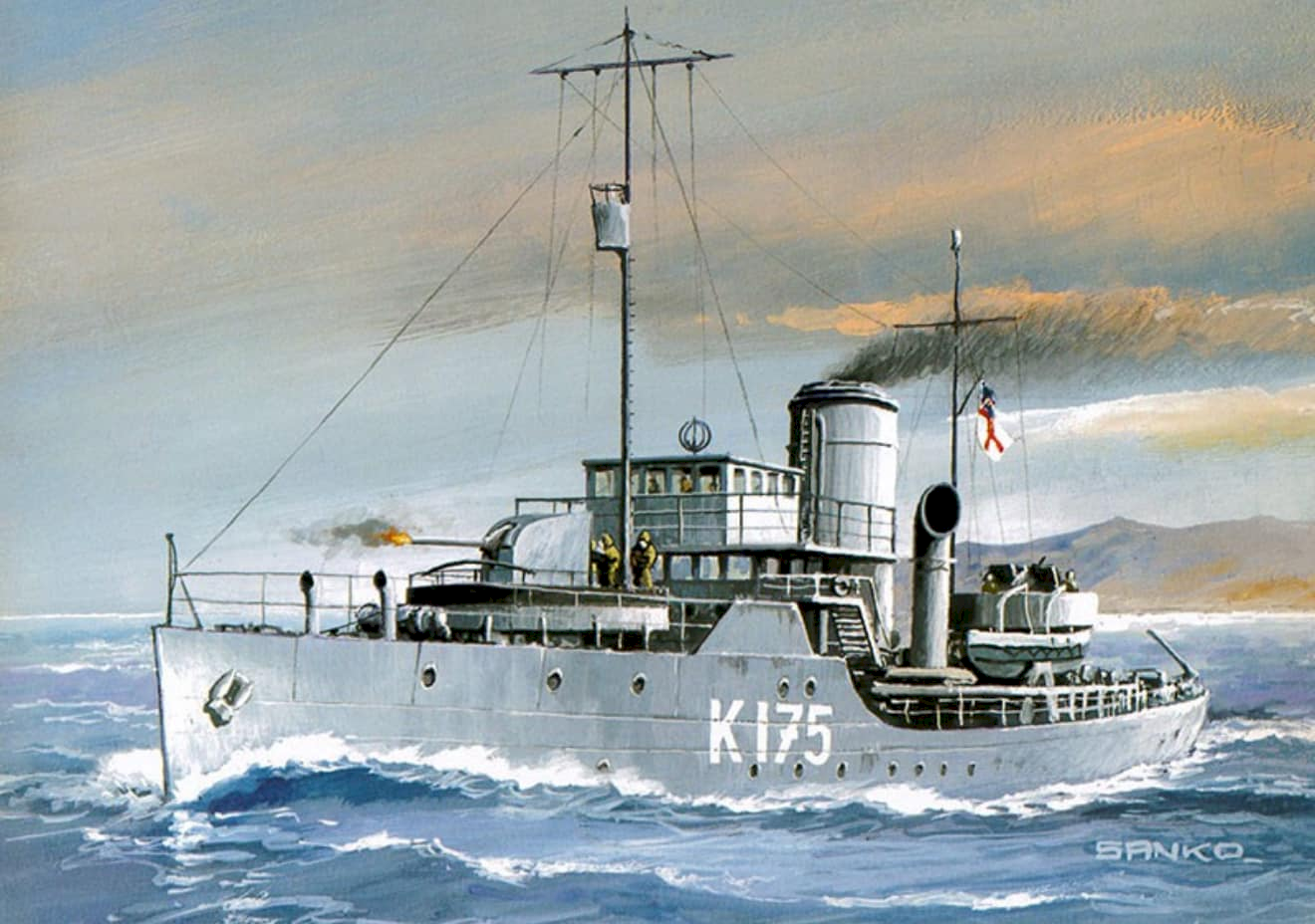

HMSC Wetaskiwin had Distinctive Design for a Warship Whaler Designed for Coastal Patrol

Warfare is a large and urgent enterprise. Re-inventing the wheel was time-consuming. Large cruisers and destroyers were complex and expensive to produce. The Allies did not have time. Naval strategists devised a plan to boost naval defence using Flower-class corvettes, a vessel already in service with the Royal Navy and well-suited for coastal patrol.

Flower-class corvettes were not as prominent as larger warships and essentially their original design was based on a whaling ship. The British Admiralty had effectively converted the Southern Pride, a 1936 whaling ship, into a warship for inshore patrol and harbour anti-submarine defence. A whaler-type vessel was admirably

seaworthy, required less resources and was quick to build.

Given the speed and aggression of U-boats, this whaler-type vessel appeared less than an ideal warship for oceangoing convoy escort. It was lightly armed with only one gun and barely faster than merchant ships in a convoy. In rough seas, it had a tendency to pitch and roll and by warship standards it was deemed not very comfortable. Nonetheless, the Allies needed warships.

The Whaler-Type corvette was an admirably seaworthy and

maneuverable vessel, cheaper and quicker to produce than frigates. It emerged as the best solution that would meet the immediate needs of both

the British and Canadian fleets.

Shipbuilding yards in the United Kingdom were at capacity. Canada's small-yet-professional navy sought to expand its fleet

quickly, as well. The Royal Canadian Navy quickly implemented an expeditious ship-building program.

Canadian ship-builders had the facilities and expertise to build merchant ships not sophisticated warships. The Whaler Type ship's shape, a simple and stout design, was similar to that of a merchant ship which allowed the RCN to waste no time in commissioning existing shipyards in Ontario, Quebec, and British Columbia to begin production.

Canadian shipbuilders had the backbones of the first British-ordered corvettes laid down in dry dock by February 1940 and four months later they launched corvettes for both Britain and the RCN. The first Patrol Vessels - Whaler Type were laid down between February and April and launched as quickly as manpower and funds allowed. (Later they built corvettes for the United States.)

While HMCS Wetaskiwin and the other Canadian corvettes were essentially the same design as the British, the Royal Canadian Navy modified it and outfitted the ship differently to be deployed as patrol vessels for the coastal protection of convoys, and they were equipped with minesweeping equipment for harbour defence.

Launching Canadian ships posed another significant challenge for Canada. The navy needed experienced seamen and professional engineers to man the ships being launched. That required increasing navy personnel from 3000 enlisted and 3000 reservists to about 15,000 by January 1941. All the ships would be crewed with junior recruited sailors who were not accustomed to naval life, had no wartime experience, and were not trained in common anti-submarine tactics. Many new recruits who went to sea had but eight weeks of training before being assigned to a Flower-Class corvette.

The term Patrol Vessel – Whaler Type did not sound warlike to Winston Churchill who was Britain's First Lord of the Admiralty at the time. In streamlining a name, he urged the vessels be called corvettes after the French and British fast-sailing sloops of war that were in service in the mid 1800's prior to the arrival of steam driven vessels.

The corvettes were further designated as Flower-class because in Britain these warships were named after flowers: HMS Bluebell, HMS Clematis. HMS Mallow, HMS Stonecrop, HMS Candytuft, etc. Apparently the British reason for naming their ships after flowers was to mock the enemy that their wolf class U-boat had been sunk by a Tulip or a Pansy. Churchill also dubbed the corvettes cheap and nasties.

The popular, sleek luxury sports car built by Chevrolet gets its name from this agile, but conversely slow and small class of warship.

By Local Artist, Scott Nelson

HMCS Wetaskiwin K175 was the first Pacific coast built Flower-Class corvette to enter service with

the Royal Canadian Navy. She was ordered in February 1940, as HMCS Banff. Her backbone was laid on 11 April 1940 at Burrard Dry Dock Co. Ltd, Vancouver, British Columbia. She was launched just over three months later on July 18 and commissioned as HMCS Wetaskiwin at Esquimalt Naval Base, Victoria. Corvettes built at the Burrard Shipyard in Vancouver cost $605,000 each.

Acceptance trials and work ups were followed by a brief time patrolling out of Esquimalt. On 17 December 1940 the HMCS Wetaskiwin received notice of war duty and ordered to report to Halifax the following March.

Rather than follow the British naming tradition, the Canadian Naval service wanted to better represent the people and establish a bond with local communities across Canada. The first 54 ships out of the docks were named after small communities: Drumheller, Kamsack, Timmins and Wetaskiwin to name a few. In the second phase of building, Canadian corvettes were named after larger cities.

Each community sponsored their named ship and played a key role in supporting the ship and its crew. Community members wrote letters, knitted socks and sweaters; service clubs assembled clothing, food, other necessities and niceties for the men who sailed under the town’s

namesake.

However many Canadian towns and cities were involved, the Flower Class label stuck.

In the Case of HMCS Wetaskiwin, Naming of the Vessel Took a Twist and Turn

Originally corvette K175 was named Banff for Banff, Alberta. Not long after she was launched a naming conflict with the Royal Navy came to light. Through Lend-Lease the Royal Navy was acquiring ten US Coastguard Cutters that would be refitted as British battleships. These ships were being classified by the Royal Navy as Banff Class Sloops in honour of a Scottish Officer in the Royal Navy, Captain George Duff (1764-1805) from Banff, Scotland. Also, though the Royal Navy had already named a Captain-Class Frigate, the HMS Duff, after this Aberdeen captain, it was their decision to name one of the newly acquired cutters, HMS Banff.

A new name was needed and another community was selected. That is how Alberta's third oldest city, Wetaskiwin, population 2200, secured the privilege of having the corvette named HMCS Wetaskiwin.

The HMCS Wetaskiwin was one of the first Flower-class corvette warships that the RCN assigned to the Battle of the Atlantic in the spring of 1941. Initially, the vessels may not have been the ideal warship, but eventually the Allies counted on Flower-class corvettes. They proved to be a formidable presence in a convoy and formed the bastion of convoy protection.

To their advantage, the 200-foot-long Corvette, not large by warship standards, had a range of 3500 miles. Naval strategists determined that the long range and sea-going maneuverability of the corvettes made them the near-perfect anti-U boat weapon and soon ascertained just how effective the vessels could be in hunting Kriegsmarine submarines.

The corvette was a better match against U-boats than battlecruisers. Her superiority was her turning circle, the tightest of all Allied warships. In fact, the corvette could out-manoeuvre a submarine. The large reserve of steam in the vast cylindrical Scotch boilers gave

the corvette a quick burst of speed, and the vessel had a

huge rudder and fine underwater lines which made it nimble at tracking a U-boat. Most critically, despite the pitch and roll on rough seas, the corvette would not yield to the stormy weather. In the worst North Atlantic raging sea, the corvette was a workhorse that could turn on a dime.

HMCS Wetaskiwin was equipped with the Active Scanning Detection and Intercept (ASDIC) system. The rudimentary electronics were a type of sonar, efficient for detecting and tracking submarines with some precision.

The vessel's armament included one 4-inch (102-mm) Mk. IX breech-loading deck gun, a 2-pounder Mk VIII 40 mm pom-pom gun and two twin-mounted .303

Lewis machine guns.

The Mk. IX was mounted on the forecastle of the Wetaskiwin. It fired a 31-pound shell a maximum of 12,000 yards. At close range its accuracy at hitting a U-boat above surface was excellent. When a U-boat was above surface miles away with only its conning tower visible, the gun's accuracy was diminished. Though, when fired it was not always a decisive weapon against U-boats, that four-inch gun was effective in forcing the U-boat down below the surface and deep.

The pom-pom gun was mounted on a bandstand over the engine room. It was designed to counter low-flying aircraft, but it was also effective against a surfaced U-boat.

The Lewis machine guns were sited on the bridge wings, also for anti-aircraft

defense.

Wetaskiwin's most feared weapon in 1941 was depth charges. If a U-boat was within range it could be pounded by the depth charges. The depth charges were designed to detonate at a predetermined depth so as to inflict damage on a submerged U-boat. Depth charges were deployed from throwers and rails at the stern.

In 1942 the Hedgehog mortar was added. It was a was a forward-throwing weapon that fired up to 24 spigot mortars ahead of the ship. It was a form of grenade deemed much more effective than the gravity-dropped depth charges which were large, slow-sinking and could only be dropped directly astern which gave a submarine time to get out of ASDIC range. By firing Hedgehog mortars ahead and by using a smaller,

streamlined and faster-sinking projectile, the Wetaskiwin was better able to destroy a

target submarine before ASDIC contact had been lost. By British calculations, during World War II depth charge attacks were effective on a ratio of about 60.5 to 1. In comparison, the Hedgehog made 268 attacks for 47 kills, a ratio of 5.7 to 1.

As the U-boat took measures to evade the corvette's weaponry, it gave the convoy time to take evasive action and try get out of range of the enemy.

The Battle of the Atlantic turned into a small ship's war, with Flower-class corvettes making up roughly half of the escorts. They were the mainstay of a small ship anti-submarine navy.

To perform better on open seas, shipbuilders modified newly built ships to perform better, and retrofitted earlier launched vessels to lessen the pitch and roll.

Between 1941-1945, RCN Corvettes were primarily focused in the North Atlantic, from the East Coast of North America to the Artic, Iceland and Northern Ireland, but were also deployed to the Caribbean, Mediterranean, Aleutians Islands and by wars end some RCN corvettes joined the British Pacific Fleet.

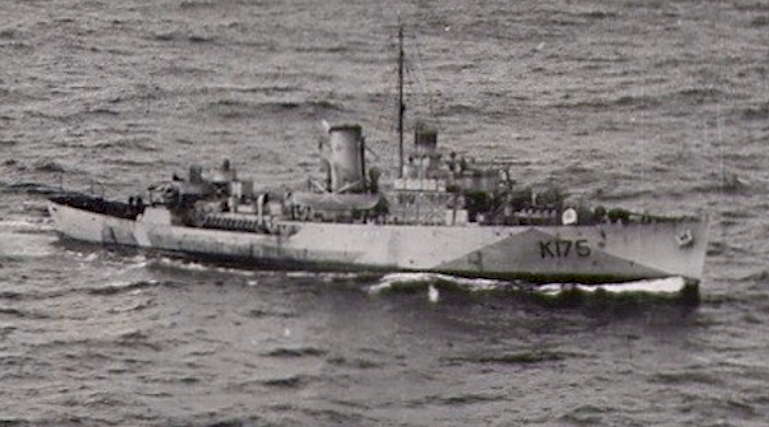

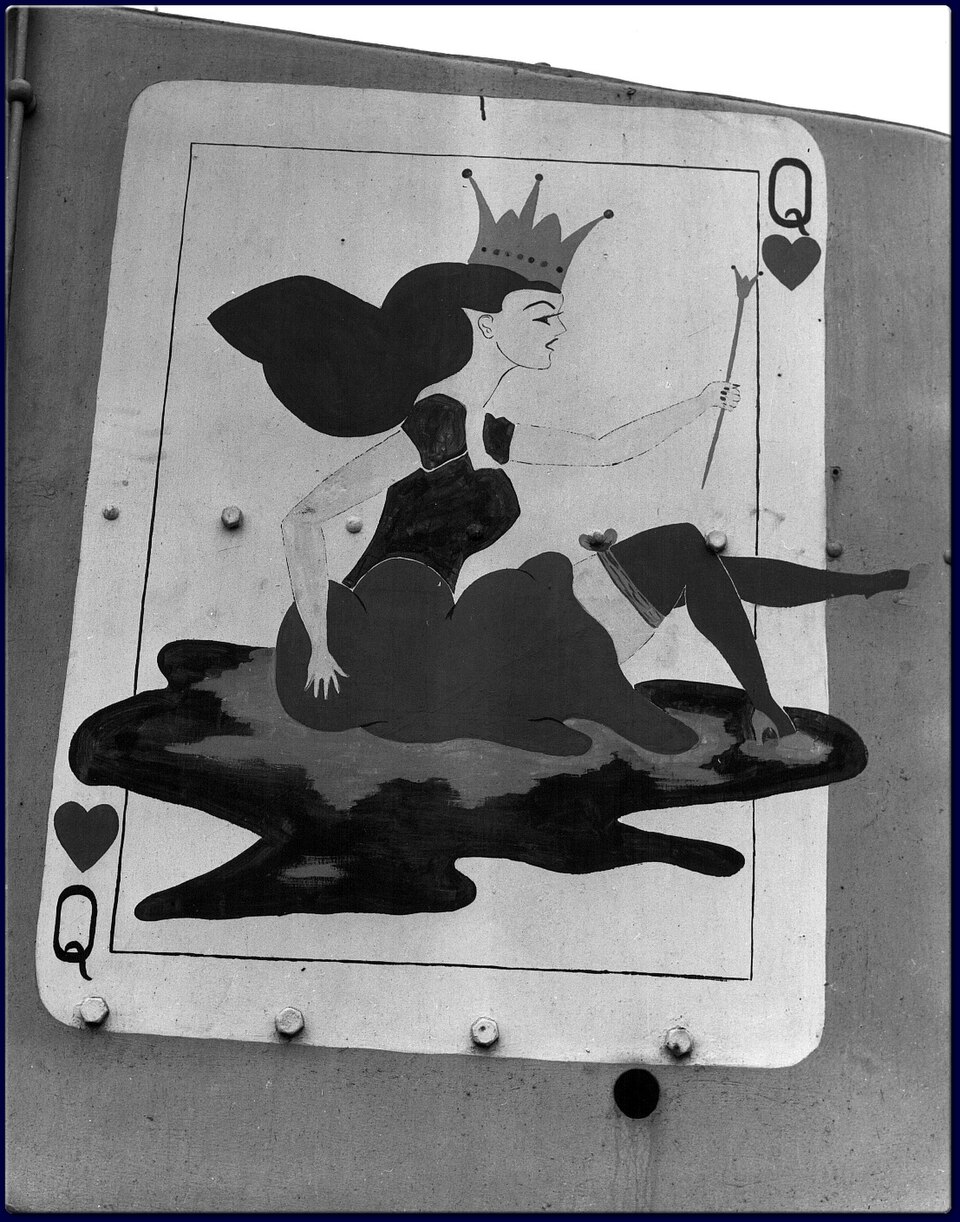

A massive 200-foot warship like K175 was not painted with its geometric patterns for aesthetic purposes. Against a featureless sky and sea, such a vessel could not be hidden from shoreline observers, passing submarines or overhead aircraft. However, it could be disguised or obscured in a disruptive camouflage scheme. Obtrusive patterns, painted on the vertical surfaces and horizontal decks of a ship confused the identity as well as the directional course of the vessel.

In the First World war, ships were painted in dazzle patterns using a bright colors such as pink, yellow, blue or green. Later, colour experts determined that the contrast between dark and light mattered more than colour because when an object is viewed at a distance the vibrant colours appear muted as shades of grey instead of their true colors. World War II camouflage experts settled on conservative hues to help ships blend into the sea around them and they chose patterns that could be at least obscured in terms of how a vessel might be interpreted.

When he is peering through his periscope, a submarine commander can be confused by some geometric or abstract patterns. That was because he did not have constant visual contact and also had to limit periscope exposure. Key variables such as distance, course, and speed

were essential for a commander to correctly position the

submarine

for an intercept. Under ideal conditions, certain camouflage designs were deceptive. For example, a warship might appear to be sailing towards the right of the viewer when actually the vessel was moving oppositely, sailing away and to the left. An aircraft pilot could adjust course and follow a warship, but a submarine commander did not have such an definitive choice and could be misled into calling off an attack.

The rapid expansion of Nazi Germany threatened the lives of millions of people. Imports of food, oil and raw materials from North America were important to Europe in peacetime; in war, these goods became a matter of life and death to millions in the British Isles, occupied Europe and the Soviet Union. To choke off these supplies Nazi German attacked merchant ships crossing the Atlantic. To defend this lifeline the Allies, particularly Britain and Canada, needed more warships and a massive injection of manpower. Ship Naval recruitment began in earnest.

In the Battle of the Atlantic, the primary role of the Royal Canadian Navy was protecting Allied convoys and hunting Kriegsmarine submarines. The constant demands placed upon it necessitated the rapid expansion of its a home navy fleet of six destroyers to 330 warships which in turn required facilities, training, support and above all, manpower. Canada's 2000 man navy was revolutionized to 100,000 personnel. Thousands of hostilities-only personnel joined the navy.

Prior to recruitment and training the story of the individuals who served on HMCS Wetaskiwin is varied. They would have shared similar experiences in naval training. The story of HMCS Wetaskiwin is a reflection on their shared experiences while serving in the Battle of the Atlantic.

In the pre-war years, adventure, travel, access to education, or a stable navy career might entice boys to join cadets. After economic downturns and widespread unemployment during the preceding depression years the navy offered financial stability. During World War II incentives might have been similar. Their stories also tell that the driving force for many navy recruits was a patriotic sense of purpose and heroism.

Newspaper editorials, recruiting posters, political

speeches and lectures from the pulpit implored men to serve. Men and women from varied backgrounds were drawn to the idea of contributing to a cause greater than themselves. Further influenced by seeing friends and family join the military, they left their homes and families to report to a naval base training site.

The compliment of the HMCS Wetaskiwin was six officers and seventy-nine crew. Many of the officers serving on warships were navy men called back from retirement. That was the case of Wetaskiwin's Lt. Commander G.S. Windeyer. Some of the crew may have been cadets from the Royal Military College of Canada. Most of the crew of HMCS Wetaskiwin and their Canadian equals were newly recruited junior enlisted sailors, who joined the service for war duties. They were called hostilities-only ratings. In other words, they left cities, rural towns and farms and reported to a designated naval training centre because they felt it was their duty. Few had ever been to sea.

In fact, 40 per cent of the navy strength came from Saskatchewan, Alberta, Manitoba and British Columbia, even though those provinces comprised 28 per cent of Canada's population.

The principal Naval Training Centre for Western Canada was HMCS Naden, one of the naval shore facilities at Esquimalt Naval Base, Victoria, a place that had served numerous military purposes for the better part of a century. Naden was surrounded by rich military history, a strong sense of tradition and also inspirational reminders of a long line of service members who served before. The Wetaskiwin crew may have also trained at HMCS Nonsuch (Edmonton) commissioned as a tender to HMCS Naden in 1941 or any one of the other RCN training bases: HMCS Tecumseh (Calgary), HMCS Stadacona (Halifax), HMCS Fort Ramsay (Gaspé Bay), HMCS Conestoga (Galt) or HMCS York (Toronto).

Royal Canadian Navy's shore-based facilities, training camps, schools, barracks, port operations, dockyards, warehouses and administration/logistics headquarters were named using the prefix HMCS (His/Her Majesty's Canadian Ship). The RCN adopted this naming tradition from the Royal Navy.

Under their Naval Discipline Act of 1866 the Royal Navy could only exact rule over officers and enlisted sailors carried or transported on a vessel. Therefore, navy training facilities and barracks were housed in old ships that were afloat in ports but incapable of going to sea. Eventually, when the Royal Navy outgrew the floating old hulks it commissioned land as ships and named the facilities as nominal depot ships. Many land-based naval facilities were unofficially called stone frigates, a term first used in 1804 during the Napoleonic War. Navy men assigned to a stone frigate were bound rules and regulations that dictate the conduct of RCN naval personnel and address various aspects of naval operations, and uphold the navy's mission.

(source: Gov't of Canada)

Upon reporting for duty a recruit exchanged civilian clothes for a military uniform, underwent a physical examination and sat for the customary haircut before introduction to an unfathomable language that was the sailors' own and indoctrination to the discipline and regimentation of the navy system.

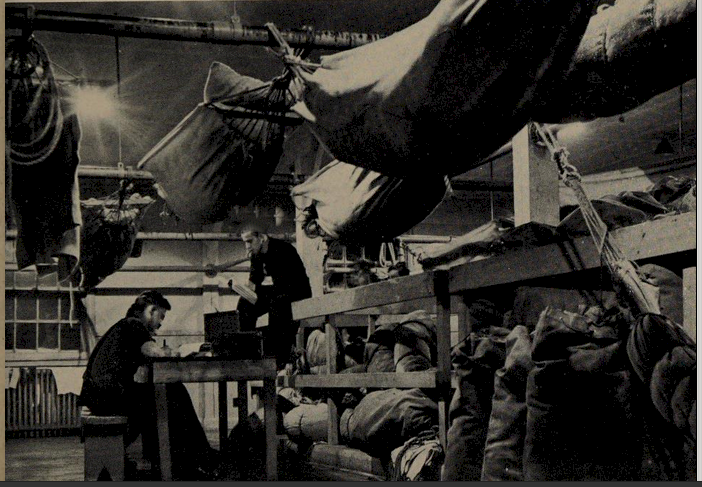

For most recruits, it was not easy to slide into the sailors' structured daily routine. They learned that flogging with a cat-o’-nine-tails or running the gauntlet were obsolete punishments. Yet, not all men were primed to obey the navy's strict orders and the discipline to live in the confinements of a warship. They had but eight weeks to become accustomed to the traditions, routines and actions to live at sea with sixty or seventy other men and the diligence to engage in battle.

What would be so completely familiar to a navy sailor one or two hundred years ago was basically built into navy traditions: how to salute both as greeting and mark of courtesy and to salute when crossing a brow onto something still called a quarterdeck; that a routine summons is called a pipe; what it meant to ring a ship’s bell to initiate the ceremony of colours; the importance of the high-pitch whistle of a bosun’s call; the precious distinction of the toasts of the day; how to salute other ships; the solemness of Taps and Reveille for military funerals; that the ship should be all spiffed up for the afternoon walk-about; and absorbing why the Naval March is Heart of Oak. Also, in those eight weeks the navy prepared the recruit for what lay ahead in the life of a sailor at sea or on shore.

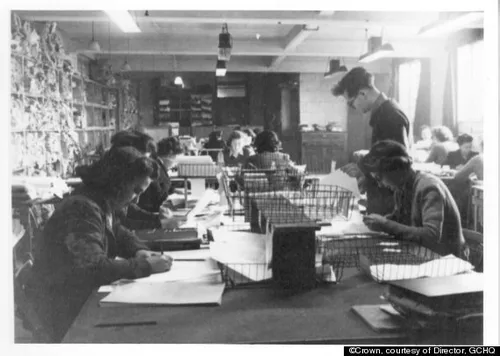

Due to the urgency of war, ratings got basic training in weapons and communications before being funneled through various other training areas to serve in either a support role ashore or combat position at sea - engineer, gunner, shipwright, supply officer, radio operator, code, signalman, mechanic, analyst etc. Training was longer and more intense for recruits that had the aptitude to be visual signalmen, coders, radar operators, wireless telegraphists, and radio artificers (skilled technicians in repairing radio equipment).

For those destined to serve on a ship, the navy concentrated training exercises that prepared ratings for the intense physical and psychological demands of living at sea. Ratings lived and trained in an environment that simulated sea conditions.

To become an able seaman ratings were tasked with learning traditions, terminology, mustering, and communication while gaining general knowledge of the ships systems and basic training in the operation of equipment, general engine maintenance, battle station positions, navigation and other at sea essentials.

They had to learn to share living space with other men in cramped condition on a ship at sea. Recruits were expected to perform jobs such as upkeep of the ship, be that cleaning or proper storage of necessary provisions.

Recruits spent a lot of time on roofed platforms to become familiar with the command centre of the ship and the communications relayed from the bridge to stations where physical control of the

ship was exercised by navy personnel. Ratings trained on a rolling bridge that rocked back and forth and sideways to simulate the pitching and the

rolling of a ship on the sea. The navy did this to help ratings learn how to maintain balance on an unsteady platform and still be able to complete tasks such as use a weapon, send legible messages, control and maintain equipment or save a life.

Recruits were expected to make good use of their time. If not on duty, recruits were expected to be proactive in honing their profession - education and preparation. They could take on challenges, learn to perform specialized duties or gain some knowledge and experience in a multitude of essential responsibilities.

Every able seaman had a job on a battle ship. Every job was vital. Every able seaman was anxious to be assigned to a ship.

K175 was launched on July 18, 1940. She went through her shake-down cruise and acceptance trials in the Pacific Ocean, at Esquimalt, British Columbia. She could not be commissioned until the navy tested her maneouverability and seaworthiness as well as verify that all her mechanical, electrical, navigation systems, and safety

features were fully operational under a variety of environmental conditions.

Esquimalt Naval Base was critical to Canada's western defence as well as a hub of naval training, logistical support, and ship building for the Royal Canadian Navy's massive wartime expansion. K175 began sea exercises with many ratings that had been trained at HMCS Naden, a Naval Training Centre for western Canada at Esquimalt.

After a brief time patrolling out of Esquimalt, K175 got its commission as HMCS Wetaskiwin on 17 December and received notice of war duty to join the Allied convoy system in the Battle of Atlantic (1939-1945).

Under the command of Lt. Cdr. Guy Stanley Windeyer, HMCS Wetaskiwin left Esquimalt on 17 March 1941 with HMCS Alberni and HMCS Agassiz on. Bound for Halifax via the Panama Canal, they stopped for fuel at San Pedro, California. While there, Canadian-born,

Academy Award-winning actress, Mary Pickford hosted a party for the companies of the three ships.

On 13 April the three corvettes arrived at East Coast Port where they joining corvettes Chambly, Cobalt,

Collingwood and Orillia.

East Coast Port was Halifax Harbour, but it was rarely identified as such. Not only the military, but the media, the city and residents recognized the extreme need for caution. They lived on the rim of danger because their port was the principal staging point for the war in Europe and lay exposed to the Atlantic. In the city, tensions were high - wartime restrictions, security requirements, night-time blackouts, searchlight

installations, air-raid sirens, Civil Defence practice, patriotic marching songs, the presence of troop transport ships reminded citizens and military alike that danger and death

lurked just beyond the submarine net that stretched across the mouth of Halifax Harbour.

The crew of K175 had very little time to adjust to the war-crowded Halifax environment. They underwent an intense, uncompromising training program under Lieutenant-Commander James Douglas “Chummy” Prentice.

Prentice had dual positions of responsibility. He was Senior Officer, Canadian Corvettes, charged with operational training of corvette crews, and he was also commanding officer of another corvette, HMCS Chambly. Prentice was a retired navy man, ranching in British Columbia when he was asked to return to service for the Battle of the Atlantic.

The navy needed an experienced saltwater sailor and forward-thinking strategist, someone astute to develop tactical doctrine for all the Royal Canadian Nave corvettes. Since the Canadian Navy was bearing the brunt and shouldering the weight of protecting the convoys against U-boat attacks, they needed an innovative and intense training program covering various operational scenarios that were mostly unfamiliar to the crews and commanders of the corvettes.

Prentice knew how to handle ships and was keen on the potential of the Flower-class Corvette. Many navy men saw the corvette as a slow poorly armed warship, a cheap vessel that could be risked in combat. But, Prentice, clever and inventive, saw the potential of the corvette as the ideal sub-hunter. He was eager to train a new fleet of sub-killers.

Prentice used a different approach to training hostilities-only ratings than training regulars. He had high standards and insisted on hard work, but he also understood that corvettes were crewed by young men who had little sea or battle experience. In other words, Lieutenant-Commander Prentice was given the tough assignment of turning the inexperienced recruits on the Wetaskiwin into trained and disciplined sailors. He had less than nine weeks to pioneer a program that would train the crews of these first corvettes for the rigors of combat in the North Atlantic, where the men would be pushed to their limits. He understood they were men fighting for their country, but they were also sons away from home for the first time and fathers missing their children. He had to prepare them to have the discipline to live at sea in adverse conditions, to acquire the technical proficiency to win a war at sea, as well as find the spirit and determination to win within themselves. Without doubt he knew they would have to learn a lot on the job in the middle of a raging war.

Prentice was keen to train corvette commanders to use one of his favourite tactics - the quick attack. Sea smart and experienced though they were, Prentice knew he was working with several ships' commanders who lacked real time battle experience.

Such was the case of Australian born Lt. Cdr. Guy Stanley Windeyer, 40 years of age, who commanded the Wetaskiwin. Windeyer was twelve when he was sent to the Naval Academy in England. At the tail end of World War One he was old enough to join the Royal Navy and was educated at Cambridge. Windeyer was a midshipman in H.M.S. Thunderer during WW I, and

was in action in the Baltic Sea. After which he was stationed in Tokyo as a language officer for the British Embassy. After postings in China and Malta he retired to British Columbia where he and his wife took up dairy-farming on Vancouver

Island,. Like Prentice, he was pulled from retirement in 1940 to take command of the corvette. Windeyer had sea smarts and war experience, but limited knowledge of battle manoeuvres against submarines.

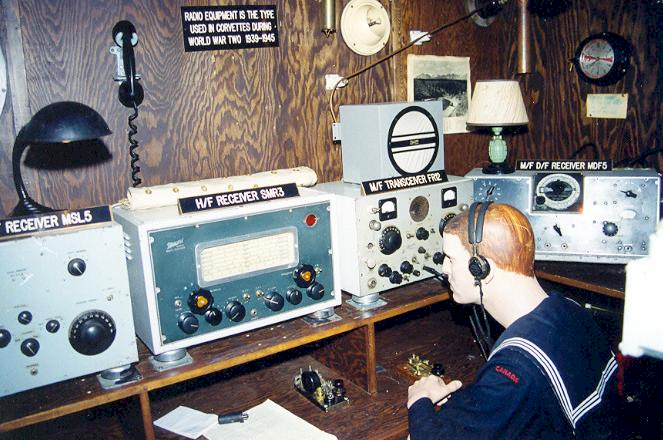

This restoration for a naval museum is close, though not 100% correct, in showing radio equipment aboard a corvette.

Training Sub-Killers

Under Prentice the crew of HMCS Wetaskiwin underwent intense training exercises at sea. Exercises took the form of warship support reinforcing the escort of convoys coming under attack. The Wetaskiwin and the other five corvettes needed to be able to work effectively to protect a convoy.

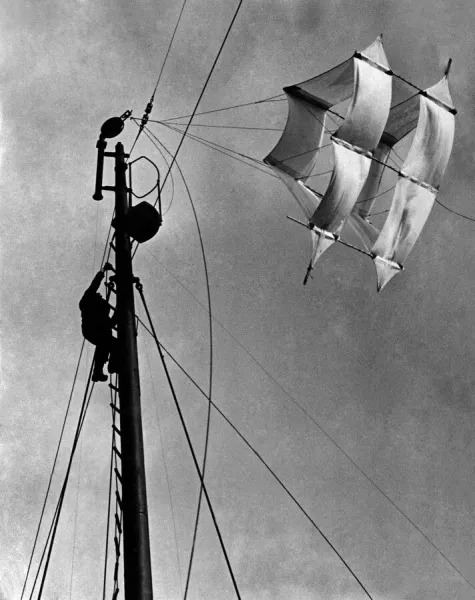

Exercises included ship-handling and days of group maneuvers at sea. Prentice placed heavy emphasis on efficient communications between the men on a ship, but more importantly the signaling between vessels. The crew of the Wetaskiwin got practical experience working with target and barrage kites, doing anti-submarine sweeps in the

entrance to Halifax Harbour and screening convoys during the first

leg of their journey out of Halifax to sea.

The most critical training the crew of HMCS Wetaskiwin received was in anti-submarine warfare. The key to such an operation is the ability of the asdic operator to differentiate marine sounds from a those of a submarine and then track that target so the corvette can gain strategic advantage and take action. Maintaining contact was vital. So, the corvette captains had to maintain their best sonar speed throughout the whole attack process and attack with precision.

In those days, there was no substitute, no simulation for using a sonar to detect and track a real submarine at sea. Prentice was fortunate to have a real submarine at his disposal for anti-submarine warfare training exercises. The Royal Navy had assigned a Dutch submarine to Halifax.

Wetaskiwin's Asdic Operators were given three weeks of ping time learning to use their sonar system to locate the Dutch sub and track its elusive movements. Meanwhile the speed of the ship could drown out the sonar and contact could be lost. Any sudden change in propeller noise could alert a U-boat of a looming attack and give the sub time to alter course or dive to the deeper. Communication from the Asic Operator allowed Lt. Cdr. Windeyer to determine Wetaskiwin's optimal speeds while getting a sense of timing and what factors constitute tactical advantage. Windeyer and the other commanders were learning to work together.

Being launched by sailor on mast.

HMCS Wetaskiwin started out with a shortage of equipment: kites and signalling equipment. The signalling equipment included 20-inch signal projectors, hand-held Aldis lamps and radio-telephone.

There were two kinds of kites used on Canadian corvettes, a target kite and a barrage kite. Crews required training to finesse working with both types.

The triangular target kite was used in defensive training. It was manually controlled by a reel and harness worn at the waist to make the kite loop, dive, climb, and make figure-eights. Emblazoned on the centre of the kite was a picture of an enemy aircraft. The kite could be extended hundreds of meters out over the water for the gunners to practice tracking the image of the aircraft as it veered about and also practice aiming and shooting at the kite as if it were a real enemy

plane.

The barrage kite was box-like with a wing span of about thirteen feet. It was strong and steady enough to hold a slender cable and pull it high up into the air where the cable could dangle for extended periods of time. If a low flying enemy aircraft flew in to attack the ship it risked flying into the cable,

which could sever a plane’s aluminum wings.

On the 6th May the Wetaskiwin had escorted that Convoy HX 125 - 40 British and Norwegian merchant vessels - to the armed merchant cruiser meeting point after which she returned to Halifax along with 12 ships that for some reason (mechanical or unstable load issues) returned to port and were scheduled to leave with the HX126, a convoy of 33 merchant ships leaving on 10th May. After more practical training, on the 16th Wetaskiwin departed Halifax with Convoy HX 127 with 46 Norwegian, Dutch and British vessels and again returned to port. Both convoys included ships carrying explosive cargo destined for Liverpool.

While Prentice was training corvette crews in anti-submarine warfare, he was also steering the HMCS Chambly through secret sea trials to test two new Canadian technologies. The first innovation was a prototype of diffused lighting

camouflage or counter -illumination to conceal ships from the enemy and the second device was Surface Warning Model 1, Canadian (SW1C) an experimental anti-submarine radar that could track the course of a U-boat on the surface. A submarine on the surface was undetectable by ASDIC.

For nearly six months the RCN had been experimenting with diffused and filtered lighting to eliminate the contrast in luminosity between a ship and the darkened sky. Submarines preferred to attack convoys at dusk or at night because when darkness appears it is never completely black; a ship stands out as a dark silhouetted target against the horizon. The right combination of lights projected onto the sides of a ship, could make its nighttime glow match its background and thus conceal its presence. In May of 1941, that round of experiments with the newest diffused lighting protype reduced

Chambly‘s visibility by 50% to 75%, enough for the Navy and National Research Council to justify development of a more robust version. Besides the advantage of camouflaging ships from U-boats, having that kind of camouflage on a corvette would allow the Allies to be more stealthy in hunting submarines and could be designed to chamelionize aircraft.

The SW1C was a combination of two technologies already in use. RCN used the Canadian designed Night Watchman Radar System to watch for enemy ships or submarines attempting to enter Halifax Harbour. The Night Watchman was permanently installed on the approaches to the harbour in 1940. It was the first radar of any design to be in operational use in North America. By combining the technology from the Night Watchman with fragments of the British aircraft-mounted ASV Mk. II radar, the RCN designed a new surface warning radar system that could be outfitted on a warship. The navy gave Prentice the opportunity to experiment with it to track the Dutch submarine as it maneuvered on the surface in dense fog under near zero visibility conditions. The new SW1C out performed traditional surface plotting techniques. Outfitted with a reliable surface radar combined with sonar to track a submarine underwater, the corvettes would be better able to track U-Boats.

That advantage was effective until late 1942, when the German U-boat fleet obtained the Metox radar detector that could detect the Canadian SW's long before the corvette's radar operators could define the presence of a German sub.

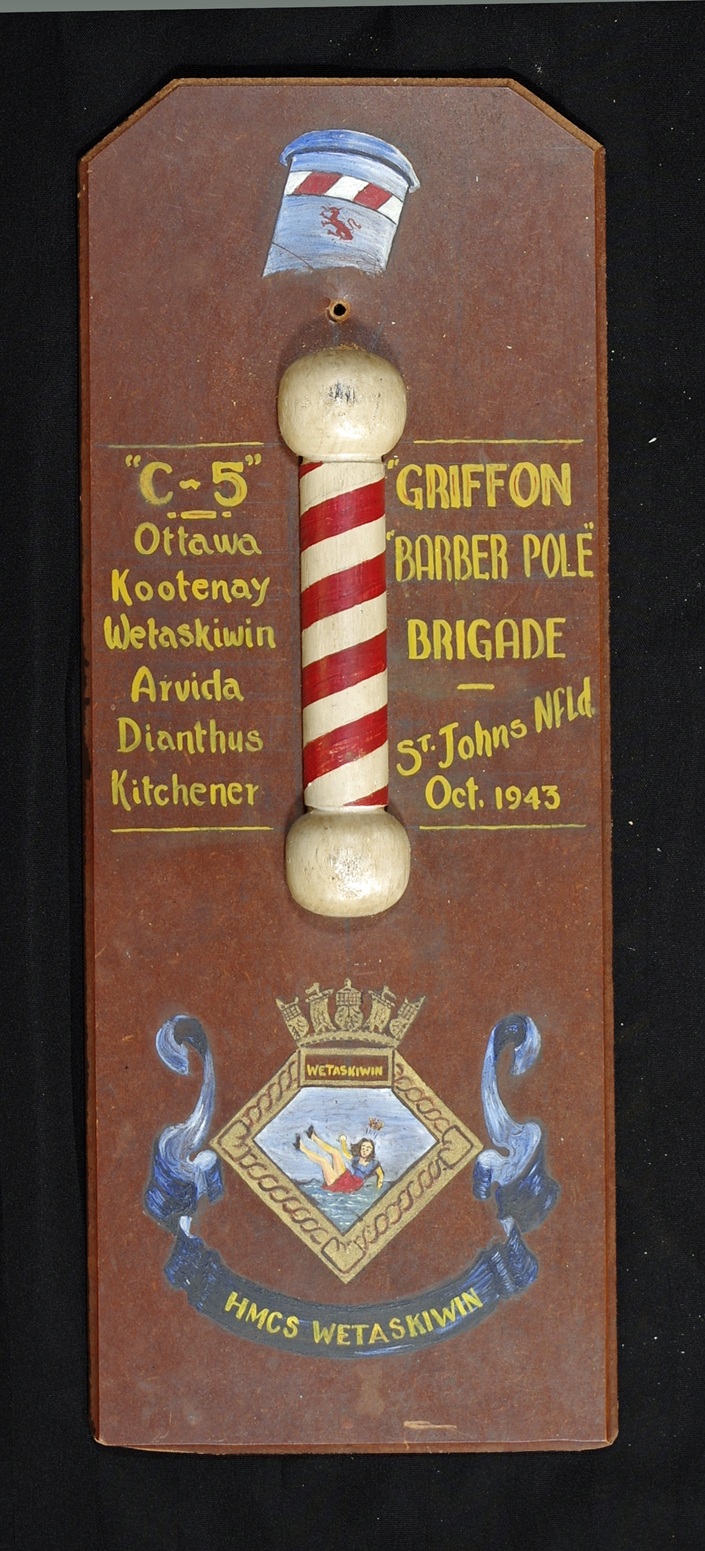

After escorting these two convoys out of Halifax, HMCS Wetaskiwin received her assignment to join the newly formed Newfoundland Escort Force (NEF), their new base of operations in St. John's, Newfoundland. The Wetaskiwin, under Lt. Cdr. Guy Stanley Windeyer, the Chambly under Prentice and five other corvettes were to form the nucleus of the NEF.

Before the Wetaskiwin departed Halifax, word arrived that convoy HX 125 reached Liverpool without incident. The British Commodore of HX 125 reported:

More ships to be fitted with kites - more kites to be supplied to ships aleady fitted and a spare wire if possible. Masters are __ to fly them but are afraid of losing their last kite. Considerable wastage is inevitable. 62 ships put up 16 kites between them. There were no kites at Halifax.

However, convoy HX 126 had been attacked by Wolfpack West, a contingent of 23 U-boats operating as one unit in the North Atlantic.

In various zones of its Atlantic crossing, HX 126 was under escort by Allied ships. The attack took place in the unescorted zone known as the Mid-Atlantic Gap. Over a three-day period (May 19-23) nine merchant ships were sunk, five of which originally were with HX125. Convoy HX 127 was still safely enroute.

Surviving ships from HX 126 reached their destination on 29 May.

By this point in the war, three merchant ships were being sunk for every one being built and eight U-boats were being launched for every one that was sunk.

On 23 May, the Wetaskiwin departed Halifax for St John's, Newfoundland with the other corvettes.

The crew of the Wetaskiwin knew they were about to engage in complicated operations that would really challenge their combined abilities. They were assigned to escort ships through the dreaded Black Pit where the deadly efficient U-boats hunted for convoys.

German Kriegsmarine sent out their warships and U-bootwaffe (submarine force/U-Boats) from their bases in northern Germany and from occupied Norway to attack Allied shipping convoys crossing the Atlantic. The Allies impeded those efforts in the North Sea by occupying the Faroe Islands in April 1940.

Iceland was a neutral country, but its location in

the North Atlantic was strategic to the Allies and the

Axis powers. To deny Germany access to another north-western base of operations in the Atlantic, Britain moved to occupy Iceland in May 1940 and set up several military bases.

The United Kingdom had also taken measures to extend the range of the British and Canadian escorts to cover more of the Mid-Atlantic Gap and by mid spring 1941 the Black Pit had been narrowed to roughly 700 nautical miles (1,300 km; 810 mi).

Germany, however, with their occupation of France and the help of Italian submarines, had found the means to move their U-boats still deeper into the western Atlantic Ocean just outside the fuel range limits of the Allied escorts vessels and aircraft. Attacks on merchant shipping were on the rise. Moreover, many of these attacks occurred south of Iceland.

It was a treacherous time. Britain's Admiralty had not figured out a way to combat against Kriegsmarine's new wolf-pack tactics where U-boats roamed the Atlantic in long patrol lines, sinking Allied warships and merchant vessels with impunity. Convoy losses were significant. Germany dubbed it their Happy Time.

By this point in the war, three merchant ships were being sunk for every one being

built and eight U-boats were being launched for every one that was sunk.

In response, Britain was forced to implement a new plan for convoy protection. First, the British Admiralty formed the Western Approaches Command under the Royal Navy - its primary aim, the safe and

timely arrival of convoys. Its base of operations Liverpool, England. Their new Atlantic strategy involved the Dominion of Newfoundland, Occupied Iceland and the Royal Canadian Navy.

While HMCS Wetaskiwin was training in Halifax, Britain deployed ground reinforcements, an infantry battalion and artillery battery to augment the military presence in Iceland to 25,000 troops.

Next, the British Admiralty called for the establishment of the Newfoundland Escort Force (NEF) as a subordinate command under Western Approaches Command. With the positioning of the NEF and a forward base at St. John's Harbour the RCN could extend coverage of the Canadian convoy escorts more than 900 kilometres further into the Atlantic, which was nearly a full quarter of the way closer to the Mid-Ocean Meeting Point off Iceland and could fill

the gap in protecting convoys between British escorts and Canadian escorts. The NEF made it possible for shorter-ranged warships and a smaller escort fleet to be used through the Mid-Atlantic Gap.

They also decided to reduce the size of the convoys and carefully coordinate convoy movements in crossing the Atlantic.

Convoys, assembled at Sydney Harbour and Bedford Basin in Halifax, were to be escorted by the Royal Canadian Navy to the WOMP (Western Ocean Meeting Point) the north-eastern fringe of Newfoundland just east of the Grand Banks. At the WOMP the NEF would assume escort duties to protect convoys to the MOMP (Mid-Ocean Meeting Point off Iceland) where Royal Navy escorts based in the Western Approached would take over escort of the convoy to Liverpool or Northern Ireland.

The Admiralty also understood the need to reinforce Allied defences in Iceland as well as in the fog shrouded waters of the Grand Banks. Canadian warships that had been deployed to convoy duty in Britain and the Western Approaches were being reassigned to bases in Canada and Newfoundland.

With all these strategic moves taking place, the British Admiralty gave the Royal Canadian Navy command of the NEF, the NEF zone and the northwest Atlantic from New York to the Arctic Circle, as well as any allied navies operating in the zone. The Canadian Navy was to bear the brunt and shoulder the weight of the U-boat war. Lacking adequate training and still not being outfitted with the essential equipment that the British corvettes had, Canada could have been reluctant to accept the request but the RCN complied with the British Admiralty's new plans for convoy protection. This was the first foreign operational command the Royal Canadian Navy every undertook.

The new Commanding Officer Atlantic Coast and in command of the NEF was career navy man Commodore Leonard W Murray of the Royal Canadian Navy. Before being reassigned, he was in command of the fleet of Canadian ships that had been dispatched to defend the United Kingdom. He was also one of the architects of the new Atlantic strategy and had strongly advocated for Canadian operations in the North Atlantic. He was more than ready to spearhead the charge towards Canada's formation of a small ship anti-submarine navy.

Murray was career navy. He joined in 1913, served throughout World War One, and steadily moved up the ranks. He served on several ships until given command of the destroyer HMCS Saquenay and then navy bases on the east and west coast of Canada. At the outbreak of the war, Murray was Director of Naval Operations and Training and was appointed Deputy Chief of the Naval Staff. He traveled across Canada convincing retired Royal Navy officers, such as Lieutenant-Commander James Douglas “Chummy” Prentice and Lt. Cdr. Guy Stanley Windeyer, to return to service for the war.

Between WWI and his commands he served on British battleships and studied at the Royal Naval College in Britain which gave him broad connections in the Royal Navy. After twenty-eight years of naval service on both side of the ocean Murray had seafaring expertise and above all he was well regarded for being definitive in terms of strategy, tactical deployment, direct confrontation with an enemy and diplomacy. He was well loved by the lower deck.

The convoy system spanned the Indian Ocean, Mediterranean, Caribbean, Arctic Ocean, North Sea, UK coastal waters, and Atlantic Ocean from South Africa to Iceland. At any one time there could be up to 20,000 people aboard the ships crossing just the Atlantic at the same time. Between 3 September 1939 and 31 May 1941, KriegsmarineU-boats torpedoed 83 ships from convoys and sank many other merchant ships that had straggled from convoy protection.

All convoys were classified according to

speed and destination.

Convoys designated as HX were British bound

convoys carrying explosive cargo (oil, munitions). Slow convoys were typically comprised of merchant vessels that were older, weather-beaten,

and prone to breakdown.

In 1941, fast convoys were scheduled to depart from Halifax or New York every six days and were expected to make the crossing to Great Britain in 13 to 15 days. Slow

convoys also departed every six days, common speed 7 knots, and took 16 to 20 days to sail from Halifax or New York to Liverpool.

H (Homebound) - convoys bound for Britain

O (Outbound) - convoys returning to Halifax or Sydney

HX - fast British (homebound) convoy carrying explosive cargo sailing from Halifax or New York

SC - slow convoys, regardless of destination sailing from Sydney, Halifax or

New York, their common speed 7 knots. From Halifax to Liverpool took about 20

days.

ON: westbound convoys sailing from Great Britain to North America

JM - convoys from British ports to Murmansk

PQ - convoys from Nova Scotia via Iceland to Murmansk

M - convoys sailing to the Mediterranean

There simply was not enough ships and manpower in the Allied defences to protect the convoys. The British Admiralty, in ultimate control of the convoy system, made decisions from a broad strategic perspective, allocating resources and manpower to fight a war that expanded far beyond the coastline of the Atlantic Ocean.

Though their reasoning might be justifiable at the time, in retrospect their allocation of resources placed Canadian corvettes in greater danger.

With a lack of properly equipped and trained vessels rotating through the command the Canadian navy was stretched to its limits. With orders from Western Approached and the British Admiralty, there was very little the Royal Canadian Navy could do to improve the quality and efficiency of the NEF or Canadian escort groups.

Canadian ships lacked crucial radar and HF/DF radio-interception equipment while the British ships were equipped with the more precise equipment. With crucial newer technologies the Canadian warships could have used the poor visibility of the fog-shrouded waters of the Atlantic to more advantage, intercepting enemy communications and track U-boat wolf packs.

Destroyers were crucial for their speed in targeting and sweeps against submarines. The RCN

was short of destroyers and those assigned from Britain were mechanically unreliable. Warships

were lost in battle or taken out of service for repairs and refits,

further reducing the available number of destroyers for escort duty. The RCN lacked destroyers. The RCN worked with too little equipment or inadequate technology. There

was very little reserve force that could be sent to augment personnel or ships. Vessels damaged by the sea or combat delayed their refit schedules, making those ships out on escort less

capable. Many of the ratings were assigned to duty with insufficient training.

NEF operations commenced with a lack of ships and fully trained manpower.

When

a convoy left a harbour it was to be accompanied by corvettes, minesweepers, and

short-range destroyers. Ideally, a convoy of 60 merchant ships would have an escort of at least 2

destroyers and 4 corvettes, a ratio of one escort for every ten merchant vessels.

Originally, the NEF Command was supposed to have sixty or more vessels at its disposal. However, operations got underway with thirty-eight warships. The Royal Canadian Navy assigned twenty-three: six destroyers and seventeen corvettes. The Royal Navy suppled an additional seven destroyers, four sloops and four corvettes. Many of those warships were still enroute when HMCS Wetaskiwin and the other corvettes reported to the NEF.

In the exigent circumstances, the RCN and the NEF had no choice but to substitute Flower-Class corvettes for destroyers. Though, by Lieutenant-Commander James Douglas Prentice's high standards, the corvettes had not yet achieved an

acceptable level of competence.

Corvettes were not to be assigned to a single convoy for the entire journey. They were to have rotating assignments, providing escort for specific legs of the voyage between Halifax and Liverpool. Theoretically, the ships of the NEF were to get at least a week for rest and maintenance between the inward and outward legs of each voyage but this rarely proved possible.

This meant that any plans for Prentice to have the facilities and time for more training exercises was also doomed. The workup training the ships and men would need before being committed to operations was an unaffordable luxury. Still, the men and ships assigned to the NEF did have nine weeks of hands-on training, more exposure than perhaps any other allied escort warships thrust ill-prepared into service in the fall of 1940.

Both Murray and Prentice knew that until more recruits could be trained and warships launched, the resources and capabilities of the men, vessels and equipment at their disposal would be taxed to their limits.

The men serving on the Wetaskiwin, like the other warships, would be under enormous pressure.

Courtesy of Rear Admiral S.E. Morison collection

When HMCS Wetaskiwin sailed into the harbour at St. John's, Newfoundland, her Canadian crew had arrived in a friendly, Allied country. At that time, the Dominion of Newfoundland was a country separate from Canada and part of the British Commonwealth.

When Britain declared war on Germany in September 1939, members of the British Commonwealth, including Newfoundland and Canada were at war, too. Newfoundland's proximity to Europe made it the first line of defence against an attack on North America by Germany. The country was unable to defend itself. From the beginning of WWII Britain placed the Royal Canadian Navy in command of the defence of Newfoundland.

Wasting no time, Canada built air bases, coastal defenses and naval facilities in Newfoundland. They expanded the air base at Goose Bay. Goose Bay was crucial for surveillance flights as well as refueling Allied aircraft. Canada built an RCAF station at Torbay (now St. John's International Airport) and expanded the naval base at St.

John's. To defend other strategic locations in Newfoundland, Canada installed artillery batteries.

One of these locations was Bell Island in Conception Bay. Bell Island was a major iron ore producer, a critical

source of raw material for steel mills in Canada and Britain for the Allied war effort. Prior to the war Germany was one of the largest

customers of iron ore from Bell Island. Of course

the Axis Powers had first-hand knowledge of Bell Island's strategic value and

wanted to cut off that supply.

The people of Newfoundland were just becoming accustomed to a Canadian military presence when in January 1941 American engineers, civilian personnel, and troops arrived in St. John's to build an American air base. The USA gained military base rights in Newfoundland at St. John's, Argentia, and Stephenville in exchange for providing the United Kingdom with fifty destroyers - a deal solidified through the Leased Bases Agreement with Britain. This agreement gave the USA a ninety-nine year lease on British territories in Newfoundland, Bermuda and the Caribbean. American detachments were stationed alongside Canadian troops at

the Gander and Goose Bay airfields, as well as in a number of smaller

communities of strategic importance, where for example radar sites were installed.

The formation of the NEF triggered another influx of sailors and navy support personnel. Within a few short weeks, the British Admiralty called upon the Royal Canadian Navy to concentrate its resources at bases in Newfoundland for the defence of trans-Atlantic convoys.

At the end of May, Lt. Cdr. Guy Stanley Windeyer guided HMCS Wetaskiwin into the busy harbour at St. John's, Newfoundland. They secured to a rotting wooden wharf at the southern end of the harbour. They had just sailed into the most highly militarized place in North America. The harbour entrance, a few hundred yards away, was the front door that opened up to the Battle of the Atlantic.

The population of St. John's had hovered at about 40,000 at the outbreak of World War One. With the appearance of Canadian and American military personnel the population spiraled to 100,000. For the people of St. John's the arrival of the ships and navy personnel for the Newfoundland Escort Force was sudden. There was little time for preparations to transition from being just a defended harbour to a major base of operations for anti-submarine patrols. As they had done in the previous months, the people of Newfoundland responded with support as best they could on such short notice.

In Newfoundland, people understood that Britain was alone in Europe. People were on rations and their freedom was at stake. Imports of food, oil and raw materials from North America were important to Britain's economy in peacetime; in war these goods became a matter of life and death to millions in the British Isles and occupied Europe. (Six months later, the German Reich invaded the Soviet Union and the convoys became the lifeline for millions more.)

Initially, the HMCS Wetaskiwin was one of twenty-one corvettes deployed to the NEF. Eventually, seventy ships home ported at St. John's. The port city was hardly prepared for the arrival of those warships and the navy crews that streamed in. But, in 1941 to the crew of HMCS Wetaskiwin, fuel, shelter,food, water andencouragement were a good start.

6 Officers and 79 Crew

201.1 ft

950 tonnes

Canadian Service 1940-1946

Commodore Leonard W. Murray had not yet made an appearance in St. Johns. He did not arrive until mid June. NEF convoy operations began on 2 June 1941.

HMCS Wetaskiwin did not sail with NEF's

first oceanic convoy operation on that day. That honour was assigned to HMC ships Chambly, Orillia and Collingwood, three ships built in Eastern Canada. Those three Flower-Class corvettes sailed from St. John's to join HX 129 off the Grand Banks. That convoy had left Halifax on 27 May. It was a 57-ship convoy heading to Liverpool. It was historic in that HX 129 was the

first convoy to have continuous close

escort all the way across the Atlantic. It arrived safely in

Liverpool on 12 Jun 41.

The RCN deployed the Wetaskiwin to the very next Convoy HX 130, also destined for Liverpool.

HX 130 departed Halifax Harbour on 1 June with 52 vessels, 18 from Bermuda and 11 from Sydney. Following the same course as Convoy

HX 129 the ships zigzaged to the WOMP (Western Ocean Meeting Point) on the edge of the Grand Banks where they would meet the NEF escorts.

Three days later, HMCS Wetaskiwin left St. John's Harbour for the WOMP with two British destroyers and corvettes, HMCS Alberni and HMCS Agassiz. At the WOMP, the NEF ships joined convoy HX 130 on the evening of 6 June. HX130 arrived with Battleship HMS Ramillies and two corvettes.

The 46 cargo ships in HX 130 were formed up in rows and columns with the ships with the most dangerous cargo bunched in the centre and the others formed up to keep beam exposure to a minimum. Ships packed in as tightly and safely as possible, but moving in formation. When the three NEF corvettes sailed into position port and starboard, the two Halifax corvettes left for St. John's to refuel. The Ramillies remained.

Their next destination was the MOMP (Mid-Ocean Meeting Point) just south of Iceland where the NEF would hand over escort duties of HX 130 to the Royal Navy and pick up a west-bound convoy to escort to the Grand Banks. The NEF ships could refuel in Iceland.

One can imagine that the shear size of a convoy with so many ships still left it exposed on all sides. With Canada's heavily armed warships serving as protection at a distance and ready to act, the corvettes maintained a steady watch, moving ahead to scout for U-boats or astern to prevent a rear attack.

Less than two hours later the destroyer HMS Burnham and the corvette HMCS Alberni detached to join convoy SC33 which was a ways off. The two warships returned on 8 June with SC 33 under protection. SC 33, a slower moving convoy, proceeded astern of HX 130, adding another 43 ships to the convoy. At that point the Battleship Ramillies left the convoy to return to Halifax, leaving two destroyers, the Wetaskiwin and the two other corvettes to protect both HX 130 and SC 33, through the Black Pit.

From the WOMP, convoy HX 130 encountered four days of dense fog with an occasional brief clear interval. Actually, poor weather and fog was a blessing for the convoy, because that kind of weather made it very difficult for U-boat operations. On the other hand, in mild weather the smoke from the funnels of the coal burning ships was very visible and a dead give-away of a convoy's location.

Had they sailed straight to the MOMP it would be about 2000 kilometers. But, to prevent a U-boat captain from determining the path of the convoy, the convoy of ships, while maintaining their formation, often sailed

in zig-zag patterns, making the journey much longer. They did so without any visible or electronic signals that might alert the enemy. At specific intervals on the clock, the convoy simultaneously executed a precise predetermined zig-zag maneouver to change course. As one main body, the ships would do this several times on their route across the Atlantic. Many different zig-zag plans were available for use and they were frequently changed, sometimes daily or as needed.

With the vast Atlantic around them the crew of the Wetaskiwin was busy utilizing their newly learned sea smarts, their expert eyes and ears scanning for danger. Crew members nervous, but on the ready.

Corvettes were often tasked with rounding up a stray ship. From time to time a ship straggled or left a convoy and proceeded to the nearest port because it couldn't maintain prearranged speed due to mechanical problems or insecure load issues. Crews had to be constantly on the alert for signs of a straggler while still hunting for a sign of U-boats.

At some point near the MOMP the two NEF destroyers left convoy HX 130 and proceeded to Hvalfjord, Iceland arriving there on the 15 June. The next day, just prior to the Wetaskiwin handing off escort duties to the Royal Navy at the MOMP, a moderate gale sprang up which forced some of the ships to leave the convoy for Iceland to secure unstable deck cargo.

The east-bound vessels of HX 130 and SC 33 were handed off at the MOMP and the Wetaskiwin arrived at Hvalfjord on 16 June to refuel.

Both convoys reached Liverpool safely. The commadore of HX 130 reported: As regards enemy activity, voyage was

uneventful.

They were fortunate because 23 submarines deployed to Wolfpack West were patrolling the area around the MOMP. The exact location of the MOMP varied for each convoy to prevent Axis submarines from anticipating their movements.

For the return trip to the WOMP, the Wetaskiwin picked up west-bound convoy OB 336. South of Greenland on 24 June, a torpedo struck the Kinross (British). All 37 crew members and gunners from the Kinross were rescued by the Royal Canadian Navy corvette HMCS Orillia. On 25 June, the commander of the convoy ordered the cargo ships to disperse. Soon after, U-boats got within range of two cargo ships - Shie (Dutch) and Nicolas Pateras Greek - and sank both. There were no survivors. The rest of the convoy escaped.

While HMCS Wetaskiwin did not partake in any one-on-one battle with a U-boat, the loss of three ships drove home what a wolfpack could do and not be seen.

6 Officers and 79 Crew

201.1 ft

950 tonnes

Canadian Service 1940-1946

Germany began the war with 57 U-boats, but only 22 had the range for operations in the North Atlantic. Admiral Karl Dönitz of Germany's Kriegsmarine understood that a lone submarine, much like a lone wolf, had its limits.

In the wild, wolves hunt with a precision that is both brutal and

beautiful. They don’t rely on sheer strength alone. Instead, they work

as a team, communicating silently, reading each other’s moves and

attacking in perfect coordination.

Their strategy isn’t just about the kill—it’s about control,

deception and overwhelming their prey before it even knows what’s

happening. This deadly efficiency wasn’t lost on military minds. ~ Scott Travers - Evolutionary Biologist

Taking a cue from nature's playbook he instituted a pack-tactic early in the war. The Germans nicknamed their submarines graue Wölfe (grey wolves) and Rudeltaktik (wolfpack) when they hunted together in a pack. In 1940, two wolfpacks patrolled - one south of Ireland and the other west of Spain. Kreigsmarine expectations were high; the nine ships they sank were not nearly enough.

Donitz's wolfpack strategy materialized in May 1941, when Kriegsmarine finally had enough U-boats for coordinated operations at sea and those operations could be micromanage by from headquarters in France.

Gruppe West (Wolfpack group West), the first Rudeltaktik deployed to the North Atlantic, consisted of 23 U-boats. They began hunting on 8 May of 1941. Before West disbanded on 20 June after 43 days of hunting, the pack sank 33 ships and damaged several others. West one of the most successful wolfpacks of World War II.

Yet, it missed HX 129 and HX 130.